The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic is the best example of a book title that squashes the pre-emptive load of its subject (well, there’s that and A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, but that’s another post entirely).

The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic is the best example of a book title that squashes the pre-emptive load of its subject (well, there’s that and A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, but that’s another post entirely).

Jessica Hopper’s anthology of music musing is sharp, righteous, and a bit sad—but sad in the way that she makes you realize that we (as women and as writers) experience male-dominated communities in so many different sectors. Between jockish editorial rooms and backstage boys’ clubs, it’s a wonder that a female writer can be as objective and searing as Hopper is about musicians—make and female alike.

It’s a rewarding read; Hopper genuinely loves writing about music, and it shows in her crisp, diverse prose and questioning of not only creative “genius”, but of artistic legacy, and sometimes the infamy therein. It also really makes you want to visit Chicago.

Bits of Note (I couldn’t call it Best Bits this time, knowing how angry/sad these moments in particular made me feel):

The opening essay, “Emo: Where the Girls Aren’t” provides a stellar intro to the writer’s personal qualms with covering an industry that seems to purposely alienate women.

The heartbreaking conversation between Hopper and journalist Jim DeRogatis on R. Kelly’s skirting of punishment when it came to his sexual predation of young girls. “The saddest fact I’ve learned,” he says, “is nobody matters less to our society than young black women. Nobody.” It’s a gut-wrenching re-telling of many, many women who survived him, only to have the legal system sweep their trauma under a rug.

Hopper’s review of MIA’s 2010 album, an article titled “Making Pop for Capitalist Pigs: MIA’s MAYA”, which gently prods at the widely acclaimed singer’s balancing act between mainstream starlet and pop terrorist: “She’s an enemy of America even as she makes music for Americans.”

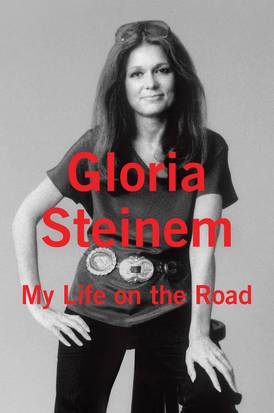

Gloria Steinem has spent her adult life jumping from place to place, from activist to journalist and back again countless times. Her name is synonymous with Second Wave feminism, and her journeys across America for the past 60 years (she’s still go-getting at 81) have kept her from getting too comfortable with any one idea about women’s place in the world.

Gloria Steinem has spent her adult life jumping from place to place, from activist to journalist and back again countless times. Her name is synonymous with Second Wave feminism, and her journeys across America for the past 60 years (she’s still go-getting at 81) have kept her from getting too comfortable with any one idea about women’s place in the world.